Interview with Camilla Sørensen &

Greta Christensen of Vinyl, -Terror & -Horror

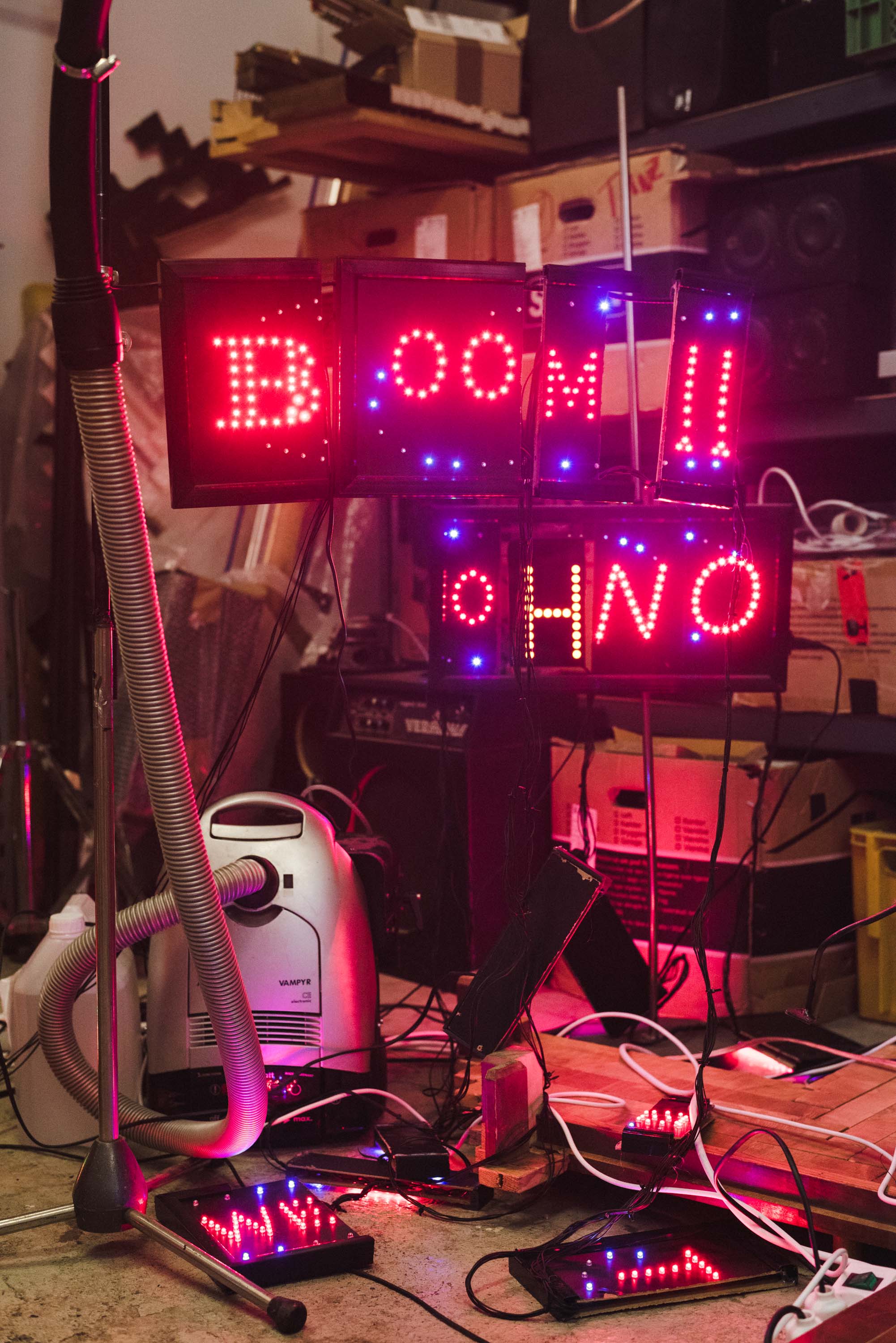

Sound as sculpture, sculpture as sound — for the Berlin-based Danish artist duo Camilla Sørensen and Greta Christensen of Vinyl -Terror & -Horror, intrigue lies in the contrast between what is seen and what is heard. Their intriguing and often lo-fi sculptures command attention and patience — before rewarding the viewer with an evocative, suspense-ridden aural journey. Ahead of their exhibition build for “Off Track” at SMAC, the artists share their inspirations and work processes amidst boxes of cut-up records, found objects and a cobbled-together smoke machine in their Pankow studio. But beware: What your eyes perceive is just the beginning.

Interview: Anna Dorothea Ker

SMAC: How did you start working together, and how did your artist name come to be?

Camilla: We started working together when we first met. We studied at the (Royal Danish Art Academy) in Copenhagen at the same time. We immediately became friends and started working together. We both made a list of things we liked. Greta played the organ at the time, and we both had that on our list, so we decided to buy one and start playing together. So it began with music. We rented a place and held a concert one month later. Music and sculptures became our main interest. We are not really musicians — we came from a background focussed on sculpture.

Greta: Sound was the common place at which we met, as we thought in similar ways. The different ideas we had fit well together into a common project.

Camilla: We also were interested in presenting our work as a concert rather than an exhibition, because that allowed for a more lively situation. So in the beginning we did a lot of performative things. The name came when we moved to Berlin in 2003 on an exchange year. We wanted to be closer to the experimental music scene here, and closer to people building their own things. We were looking for a name for a while, because it's a bit boring to be called "Greta and Camilla”. We saw a flyer for a concert we were playing at. Under our names was a description of our style — it was called "Vinyl Terror". We just picked that as a name and added the "Horror" to it to give something extra. Because it's not only terror. Terror is destroying things. It's a different energy. Horror is more atmosphere, more psychological.

“Terror is destroying things. It’s a different energy. Horror is more atmosphere, more psychological.”

What can visitors expect to find upon entering SMAC for your exhibition "Off Track"?

Camilla: So here we have the motorcycle, which is the first thing visitors will see when they enter the gallery. It was originally made for a library. The piece has a function where you put the sound to the film in the studio afterwards. There's this screen that's showing a video clip of someone saying “shhhh” but instead of the sound of the video you have a mechanic working on the wheel to let the air out. Then there's a compressor filling it up afterwards. For this show, we've rebuilt it a bit.

Greta: It's supposed to create the sound that we first hear: silence. It's a huge machine, and the compressor will start once in a while and make a lot of noise, just to fill up the air in the back wheel. So the work is ironic in its construction — it punctures itself. But that's all we can say about it for now.

How does this exhibition fit into the trajectory of your practice in general?

Greta: We work with sounds and objects that are shown in very different ways. With the bike, we're producing the sound ourselves. Whereas the sounds upstairs are made on a computer. In any case we often use elements from past works and drag them into new connections. A new narrative, so it becomes a small element of a bigger thing which we cannot describe yet, as the work finishes when we set it up. This is the way we work — it's not about having a fixed idea. The concept develops over time, and we blend together the different elements that arise as we create it.

Camilla: Upstairs in the gallery will be the piece called "Off Track", which we've shown before too, in Denmark. But we like it so much that it deserves to be shown in Berlin too. With "Off Track", there are a lot of very dramatic movie samples, it's very low fi, then there’s the technology of the speakers crashing, which is accompanied by the soundtrack of a movie where there are trains collapsing into one another. At that point, the speakers are doing the same thing. With the motorbike, it's the reverse. There are silent movie clips, then the sound is made by the effect of the sculpture. There's this huge machine, just to create the sound of silence.

Greta: There are elements that we have reused and combined. For example, the vacuum cleaner is attached to a smoke machine. When everything collapses at a certain point, there's a strobe that switches on underneath and a sound system that builds up to a climax. We had a construction where one of the speakers was moving and the other was standing still. But this is a new construction, and has a new function.

How do you approach the process of collecting and archiving?

Greta: We have a huge bunch of cut up records, then a huge library of samples from movies on the computer. The idea is that the listener should never know which film it's from. The fact that it comes from an already fictional story, a narrative — of course you can record the sound of a door squeaking in a basement. But we like to take them from other stories, and then add further elements that could lead to new ideas. Short moments of these stories which refer to simple situations that you can easily understand and visualise in your mind, like the door, or footsteps. If you put them in a certain order later, in an installation, your mind will try to organise them into a story, even though it might never have occurred. Then there are all kinds of other sounds, which are much more abstract. And some of them are also from records, like classical music, opera, but also "Schlager" and pop. That's why we use vinyl — you can take what's available, and then fit the records to the situation. We don't just use the material as it is; we put our own fingerprints on it.

Camilla: In this piece there's also going to be a structure upon which a turntable is standing, and at one point it will receive a signal to play. Then it starts playing a long song — some happy Schlager music. There’s also a motorised broom that taps like an angry neighbour who lives below you. It makes the needle on top skip, as the record player is very sensitive to abrasions, and so maybe the needle jumps a few tracks. So it's also a way of using machines to randomly compose something in real time. Then there are other parts in the piece which will start playing at a certain time. There's this record that Greta shot with a gun and cut a piece of music into it. Then we have a combination of two cut up records of violin music that have been glued together, then we recorded it and gave it to a violinist to transcribe it and play it again, without all the cuts and jumps of the needle, so that it becomes one piece, a new piece for violin, but one that's very off when you hear it. But when you don't hear the jumps and cuts you can start to accept it as a piece of music. On the screen you see a singer singing a song while being pushed from the back. The speed is thirty-three beats per minute, the same speed as the record, because the record is trying to translate a cut-up version of a record that's like a spiral, where the needle jumps as well.

Is it fair to say that abstraction is a recurring theme in your work — so as to allow viewers form their own narratives?

Greta: That's fair — although there is a beginning and an end, which very much goes towards an ongoing story that you can only understand in the context of a starting point and a resolution. The loop is seven minutes altogether, though we might break it up a bit.

“The image is the same, but the ideology is different.””

What are some of your favourite places to search for the objects, sounds and snippets you use in your work?

Camilla: eBay, for example (laughs). It's an easy way to just sit at home and find things without having to drive around to second hand stores to get the thing you need. But that’s when we know what we're looking for. We also drive around on two big bikes with carriers at the front so if we pass something useful on the street, we can take it with us. Then there are the flea markets. Sometimes we also get given speakers and old record players from friends. Everything that ends up here in the studio could get cut in half at some point. Even when an installation of ours is finished, there's still the possibility that it will get reworked and appear in another version when we get new inspiration. It's not like we produce a piece, put it in a box, and declare it done. After a few years works might become materials again. Unless someone buys the piece, of course!

Greta: When you see technology not working, either you want to touch it, or you wait, you know?

Have you always been interested in building things, or has the DIY-approach come from necessity in light of the projects you want to realise?

Camilla: We've always been doing it, and over time we've improved, but in some cases we have other people building for us too, because we want our pieces to last forever. Which is hard to achieve!

Greta: Speaking of necessity, it often goes like this: we have an idea that we need to realise with programming and so on — so we learn what's necessary to make it happen. Then we need to do something else, so we learn that. It's about focus, and about prioritising where we put our energy. The aim is to realise our ideas, not to become technical wizards.

“... we work to make the sculptural side and the sound element inseparable. The sound and the object are on the same level.”

And of course, a lot of the technology you work with could be seen as retro or old-school.

Greta: Yes, but that part is easier for us to grab onto and go into and modify. Because it's about mechanics. We can take it apart and put it together in a different way. As soon as we start with computers, it's a different kind of work. Then it becomes about working with sound as sculpture. Everything's very physical, including the preparation of the sound. Because that's something you cannot do with a computer. We use the computer to run the whole thing. But you don't see it, you don't have access to it in a sense. It just makes everything run at a specific time, and in a specific order. The pieces always refer to themselves, for example — the movement of the speakers is the movement of the sound of trains colliding. Sometimes the sound works with a piece, and sometimes against it, as a contradiction, but we work to make the sculptural side and the sound element inseparable. The sound and the object are on the same level.

“Because we work with all this found, old material, it’s a bit trashy and a bit clumsy sometimes. Then you add this sound which is so dramatic and has so much suspense to it, and it navigates how you experience the whole piece.”

What are your personal favourite film soundtracks?

Greta: I really like the soundtrack from The Shining, by the composer Penderecki. The Exorcist is also very nice. The sound has to work with the movie, and that's what's so nice about horror films because the music gets so much space that it's at least 30% of the movie in most cases. You work with sound on the same level as you do the pictures. For most movies, it's always about finding this balance when you work with images that the sound doesn't take over. The pictures are valued the most, and the sound has to navigate around it and support the pictures. But in horror movies, it often works the other way. With sound you can trigger so much in the human mind, whereas pictures are more dictatorial. Because we work with all this found, old material, it's a bit trashy and a bit clumsy sometimes. Then you add this sound which is so dramatic and has so much suspense to it, and it navigates how you experience the whole piece. If it were just sound, it would perhaps be too much. The sculptures pull it all down to earth again. So we can work with these different elements — or the other way around. To a perfect speaker we can add very destroyed sound. It's always about the contrast. You can't actually see the images conjured by the sounds, but they're there in your mind. So it's about trying to reach out a little bit and use the stories the sounds bring, but also the atmosphere, what it triggers.

Camilla: When a very atmospheric horror music is playing, it really lifts up the clumsy solutions you see in front of you, out of their material and into something else. And it adds a touch of humour, to have these two very different sides.

Interview: Anna Dorothea Ker

Photos: Luke Marshall Johnson